Biting the Apple

The Psychology Behind the Biblical Story of Creation and the Fall of Man

Introduction

Myths, legends, and folktales are effective tools for illuminating aspects of the human psyche that would perhaps escape our notice. Carl Jung, one of the earliest pioneers of psychoanalysis, believed as much and devoted a great deal of time to divining meaning from these tales. Perhaps the most crucial discovery he made during his research was the striking similarities in both themes and symbols among stories throughout history and across cultures. This revelation was instrumental in the formulation of his theories of the collective unconscious and archetypes.[1] The collective consciousness, according to Jung, was an aspect of the unconscious human mind that was present throughout the human species. According to Jung, it is the most primordial aspect of the human mind, ensconced in the very core of our psyche. Archetypes were symbolic representations of human unconsciousness.[2] Such archetypes could take human form, such as heroes, magicians, or tricksters. They can also manifest as things like snakes, trees, fire, water, the sun, and the moon. These archetypes are symbols of concepts universally rooted in the collective unconscious and are routinely found in myths, folktales, and legends around the globe. They are the lexicon the of unconscious mind, and stories are the way by which our unconscious speaks to us. In fact, has been suggested by recent research that the unconscious mind plays a pivotal role in all creative work.[3] Indeed, our unconscious routinely makes forays into our conscious mind through either dreams or our creative process during waking hours. However, the unique properties of folktales, myths, and legends, bear an even greater depth of meaning. As Canadian clinic psychologist Jordan Peterson argues, such stories have undergone a centuries-long process transcending ages, by which they have been both saturated with symbolic meaning and shorn of superfluity. The result is a multi-layered anecdote reflecting the collective unconscious, riven throughout with priceless insights about the human condition.[4]

The Book of Genesis: A Wealth of Primordial Expression

The Book of Genesis is no exception to this theory. While the apparent purpose of the book is to explain early history from the creation of the universe to the arrival of the Jewish people to the Promised Land of Canaan, its veracity as a literal history is upheld mainly by Biblical literalists. Genesis stands out among other books in the Bible as the most outwardly fantastical, and even some Christian scholars are beginning to reject its historicity in any strict sense.[5] Yet this does lead us to dismiss the text as nonsense. Rather, the stories of Genesis are a collection of archaic tales, many of which are believed to have their origins in prehistory and to have undergone a series of revisions over time.[6] This suggests that, far from being fantastical monkeyshines fermented and spewed from benighted bronze-age minds, the stories of Genesis are priceless expressions of the human psyche; a well-aged vintage of psychic craftsmanship imbued with, perhaps as St. Thomas Aquinas believed, an inexhaustible depth of meaning.[7] The creation myth, spanning from the formation of the universe to the fall of humanity in the Garden of Eden, is a prime example of the hidden message dwelling below the surface, and will be the focus of this article.

A Summary of the Story of Creation and Eden

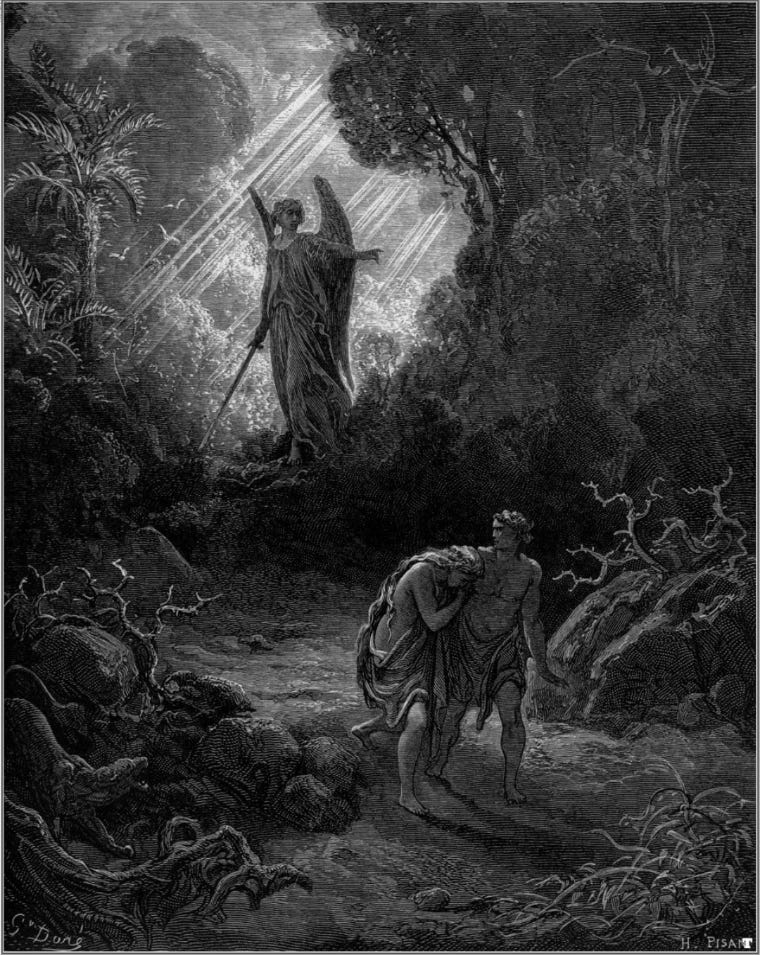

To understand exactly where this hidden meaning lies, we must first be familiar with the story itself.[8] The fast and dirty version of creation myth as depicted in the Bible states that God created the world in seven days, where on the sixth, he made humans, and on the seventh, he rested. At first, God lived and walked among them in a paradise that he created for them, called the Garden of Eden. At this time, the two people were completely innocent and without knowledge of good and evil. However, there was a fruit-bearing tree in the garden that God had forbidden them to eat from, under the pain of death. Eventually, however, Eve is convinced by a serpent – presumed to be Satan by later scholars – to eat the fruit anyway. She then brings the fruit to Adam, whom she convinces to partake of the fruit as well. After eating the fruit, the two are struck with a new sense of awareness, first manifesting as the horrifying realization that they are naked. Because of these new feelings of shame, they hid from God as he approached them in the Garden. Yet God soon discovered them, and once he confronted the couple, they confessed that they had eaten the fruit against his directive. As a consequence, God banished them from the garden and condemned them and their descendants to a life of toil, while stripping the snake of its legs as punishment for deceiving the credulous humans.

Interpretation in a Collective Sense

One theoretical interpretation of this story is that it is an allegory for humanity’s acquisition of reason and self-awareness. The myth characterizes this evolution as humanity’s downfall and the beginning of their suffering places it in a tragic light. This suggests that humans unconsciously consider its sentience burdensome, and therefore, the account of Adam and Eve’s fall in the Garden is an allegory for the onset of human neurosis.

In this sense, the “Garden of Eden” is not a real place, but an allegory for a state of mind. Adam and Eve, the archetypical humans, initially lived blissfully and unencumbered by any moral sense or acute sense of self. Free from the associated emotions of guilt or capacity for suffering (one must be self-aware to suffer, as it requires a mental capacity for reflection) they lived in a metaphorical paradise.

The two humans’ decision to eat the fruit that led to their awareness of good and evil, can be understood as a fictional explanation for an event whereby Adam and Eve – apart from any other possible humans alive at the time – developed a sense of self – awareness, the kind also needed to weigh value in a manner that includes “good” and “evil”. From here, feelings of guilt, anxiety, guilt, and regret crept in. This development made it possible to conceptualize death. Henceforth, the now sentient humans would be haunted by the specter of their own mortality. These new qualities irrevocably changed the way Adam and Eve saw and understood their world. The shameful realization of their own nakedness marks the end of their unadulterated happiness and the beginning of their torment at the hands of their own minds.

The emergence of sentience also marks the onset of humanity’s alienation from its ideal self. Adam and Eve were confronted by God, who banished them from the garden and them to toil the Earth and suffer under its austerity. In this sense, God is not a deity per se, but a symbol of man’s view of an ideal self, just as the garden was symbolic of innocence. Beforehand, humans harbored no moral standard to weigh themselves against, nor the capacity to judge themselves in any critical way. Because of this, they and their ideal self were united. There was no expectation of meeting a criterion, nor any trepidation over whether or not they could stack up. With the onset of self-awareness, however, humans gained the capacity to judge themselves objectively against an external ideal, from which there is always a difference. This precipitated the rise of feelings of inadequacy, shame, guilt, and self-rejection that we now find so common in the human experience today. The fall of Adam and Eve in the Garden is the myth that symbolizes when the human consciousness is transformed to where it is acutely anxious about death, ashamed of its separation from his ideal, and plagued by suffering. This is the true “original sin” of humankind.

As an Allegory for Individual Development

Adam and Eve’s fall from grace can also be understood in terms of our common life cycle. In this sense, the story focuses on the individual’s journey through the ages, beginning as a happy child, oblivious to shame, guilt, or sorrow, to its gradual loss of innocence as it approaches adulthood. From the vantage point of this myth, we can share our feelings of longing for the lost innocence of our youth. Our own experiences with this phenomenon also serve to connect with the concept of sentience in terms of an evolutionary event.

Few adults remember much about their childhood before a certain age, and we remember even less of how or what we thought. By contrast, we can remember, with bittersweet nostalgia, the spectrum of pure, unadulterated emotions that we felt as children. When we were happy, we were exuberant, untainted by the worries and woes of the world. When we were sad, we pulled no punches, and let it all out. And when we were angry, we got good and angry. Almost without exception, the innocence of our souls was matched by a purity of feelings, free of anxiety. We were blind to guilt. Finally, we did not suffer as we do as adults, a persistent misery that so often brings us into submission, pushing us toward suicide or mental illness, or driving us into the duplicitous embrace of religious devotion or some “higher purpose”.

Yet adulthood, “the serpent”, comes for us all. Anthropologists assert that humankind, despite drastically altering its environment over the centuries, have hardly changed in biological sense at all. It is therefore likely that this psychologic shift from the innocence of childhood to the state of constant suffering and dissatisfaction experienced by adults at least as far back as the dawn of civilization. It would make sense, therefore, that ancient humans described this feeling in the form of an allegory, specifically that of Adam and Eve. Again, the Garden of Eden, a place of eternal happiness and plenty where death is unknown, represents the unadulterated souls of children. In this case, however, Adam and Eve eventually gain knowledge of good and evil, and once they do, are deprived of their innocence and are relocated a new environment replete with toil and tragedy. God, in this case, again represents the external moral standard, which tyrannically lords over our hearts and minds with its commandants.

Conclusion

This interpretation of the age-old myth sheds light on the way ancient humans perceived their unique place in nature. As a story, it expresses humanity’s awareness, as moral and rational, and that his psyche is fundamentally different from his fellow organisms. It also demonstrates ancient man’s awareness of the cost of his special attributes, specifically our acute propensities for guilt, suffering and anxiety. Finally, it is perhaps one of the earliest examples of the symbolism of God as a representation of the human ideal, and that once man is capable of judging himself against his ideal, and upon identifying the differences, he feels a new sense of alienation from it, resulting in the externalization of his ideal self, i.e. the creation of God in man’s image.

The archaic legends, myths, and folktales, found in the Bible, are gateways into the psyche of the ancient human mind. The enduring relevance of these stories speaks to the consistency of our nature over time and the opportunity for us to glean insight from them. As Carl Jung once posited, these tales are a reflection of our psyche, and riven throughout with symbolism drawn from our unconscious. It is the mode by which it speaks to us. We need only pay attention and listen.

[1] https://iaap.org/jung-analytical-psychology/short-articles-on-analytical-psychology/the-collective-unconscious-2/

[2] Jung believed archetypes themselves were limitless. However, the presence of these representations was ever-present in the collective unconsciousness.

[3]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3115302/#:~:text=The%20creative%20process%20is%20characterised,as%20a%20self%2Dorganising%20system.

[4] https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2018/04/21281/

[5] https://www.npr.org/2011/08/09/138957812/evangelicals-question-the-existence-of-adam-and-eve

[6]https://www.college.columbia.edu/core/node/1756#:~:text=The%20disputes%20between%20the%20northern,in%20the%20book%20of%20Genesis.

[7] https://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2018/04/21281/

[8] Genesis does, in fact, begin with two creation myths, placed side by side in the Scripture. This is likely due to editorial deliberations made during transcription from earlier texts and oral tradition. However, the details of the events of creation itself are not inimical to the substance of the rest of the story.

Excellent piece, dear Animal! You’ve detailed the rich symbolism in the story wonderfully. I’m also very glad that you touched on how we each experience ‘The Fall’ for ourselves as we progress from the innocence of childhood to adulthood. We gain knowledge, at great cost. This is a profound insight that I’m hoping to write more about myself in the future!